- Home

- Our Vision

- Leadership Team

- ICPH Services

- Public Health Desk

- COVID-19 Response

- Nurturing the Spiritual Development of Children

- Toolkit poster

- A concise summary of the workshop

- Overview of Educator’s Training

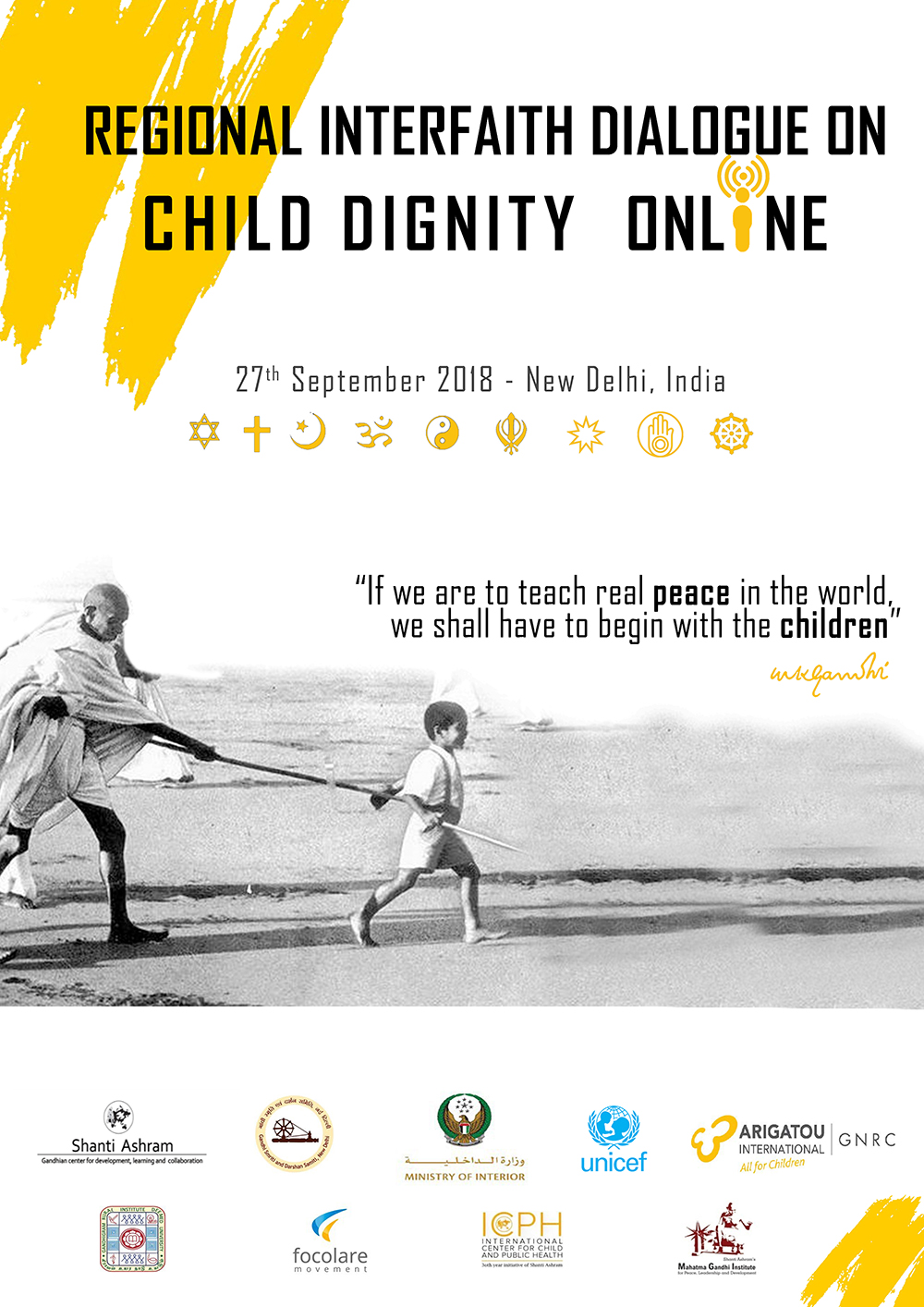

- Presentations from the India Team

- Classroom Implementation – Observation Analysis at Bala Shanti Kendra’s

- Overview of Bala Shanti Children’s Parent Sessions

- Glimpses from the Educator’s Dairy

- Reflection of the Focal Lead in India

- India Photo Gallery